A Man of Vision

Born in 1844, N. O. Nelson was to prove himself a true child of the industrial revolution, although he was born in Norway, he grew up in rural northwestern Missouri after immigrating with his family to the United States at the age of two.

In young adulthood, Nelson left the family farm and joined the Union Army. As the Civil War drew to a close, the prospect of a reunified nation opened new potential for industrial and economic development. Determined to seize the opportunity, Nelson headed for St. Louis, by then a thriving commercial center.

In an age when vast fortunes were made at the expense of labor, Nelson emerged as an industrialist with a finely tuned conscience. He was exceptionally well read, a man of ideas as well of action. He was a Unitarian, imbued with strong values regarding the fundamental right of man to live in freedom and dignity.

As an arbitrator in an 1886 railroad strike, N.O. Nelson was directly confronted with, - and repelled by- the callous attitude of management toward workers. The exploitation he witnessed and the violence sparked by the strike turned him to seek a remedy to the capital/labor conflict which he could implement in his own company.

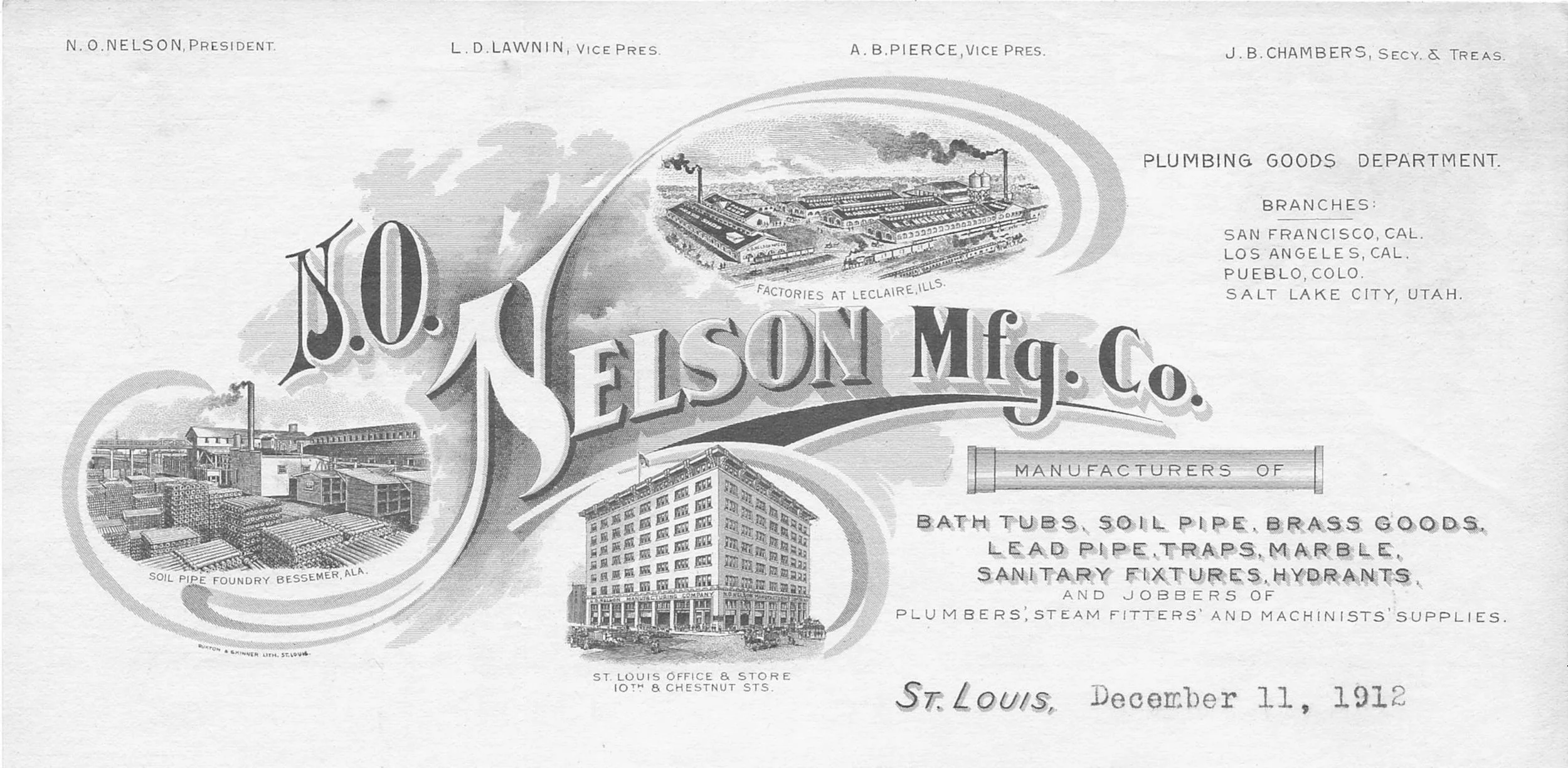

About this time Nelson read Sedley Taylor’s book, On Profit Sharing Between Capital and Labor. He believed that this book had an answer to the social and economic problems of the factory system. It suggested a solution to Nelson, and he soon announced his own profit sharing plan to employees. He visited a number of industrial villages in New England and Europe and, by 1888, had determined to relocate the N.O. Nelson Manufacturing Company to a rural area. Around the factory, he would construct his own model village.

Drawing on earlier examples of the cooperative movement and profit sharing, he pursued what he saw as a middle ground between capitalism and socialism. His intent was to create a total environment that would foster contentment for those who lived there. The name for his enterprise, Leclaire, was chosen by the workers and came from Taylor’s account of the house of Edmund Leclaire in Paris, France, one of the pioneering experiments in profit sharing.

A Place to Build

By 1890, Nelson had located a site for his factory and village on the outskirts of Edwardsville, Illinois. Seeing the economic potential of Nelson’s plan, Edwardsville businessmen and residents enthusiastically pledged $24,400 in cash subscriptions and land contributions to further the project. The land would be turned over to Nelson as certain phases of the development were completed.

The 150.5 acres ultimately secured by Nelson was fairly level, favorable for plant and residential construction. Tracks abutting the factory grounds provided access to several major railroad lines. A near by coal mine supplied fuel, and a sizable pond provided both water for the plant’s boilers and recreational opportunities. It was ideal.

The Factory: A Model Workplace

Nelson’s first priority was the erection of the factory buildings, hiring of workers, and the production and shipment of goods. The first parcel, 27.5 acres, was conveyed to Nelson on April 29, 1890.

A. E. Cameron, a prominent St. Louis architect, was hired by Nelson to design a remarkable manufacturing facility which stood in marked contrast to other factories of the time. The single story brick buildings were spacious and each housed a separate manufacturing function- machine shop, marble shop, cabinet shop, brass shop, and varnish shop.

Skylights topped the buildings, and the walls were lined with large, arched windows, which flooded the work space with natural light and opened to admit fresh air. All buildings were equipped with electrical wiring, a sprinkler system for fire protection, and ice water for the men. The grounds were landscaped with grass and flower beds, and screened from the rest of the village by a hedge of Osage Orange Trees.

“As I walked through the factories, I looked at the men. It is generally easy to judge a man’s condition by his face...the workmen in the Leclaire factories were working away as if work was a pleasure”

Beautification

South of the factory was a 2.5 acre tract for baseball, football, tennis courts, and a bowling alley and theater. Adjacent land was set aside for a school building known briefly as the “Academy.” The remaining land was designated for residential use with the exception of an existing farm which continued to be used as the Leclaire farm and dairy.

As Nelson turned to development of areas beyond the factory, he sought the talents of Julius Pitzman, the St Louis City surveyor and civil engineer who oversaw the development of Forest Park in St. Louis, Missouri.

Pitzman’s design called for a tree lined curvilinear street system and residential lots averaging 15,000 square feet. Unfortunately, after 1900, lot sizes were reduced and new streets laid out on a grid system. He also introduced the concept of deed restrictions which limited uses to houses and schools. He had concluded that to produce “artistic” effects in residential areas it was necessary to develop large tracts of land with a 30-foot setback of houses from the street.

Nelson believed landscape has a shaping influence on character, and Leclaire was designed as a garden community. Open areas around the factory were planted in grassy lawns and flower beds, and a border of Osage Orange Trees screened the industrial area from the residential portion of the neighborhood.

Nelson actively promoted gardening, setting the example in his own yard. Free plants and flowers, grown in the company’s steam- heated green house, were offered to anyone who wanted them, and each year, prizes were awarded to the best gardens.

The Residential Area

Nelson attributed much of the dissatisfaction among factory workers in the cities to inadequate housing and the hopelessness of home ownership. He determined to place home ownership in Leclaire within reach of all who wanted it. Generous building lots could be had at a fair price – purchased on installment, with payments adjusted to a man’s wages and the size of his family.

If a worker desired, the company would build his house for minimal profit over the cost of building materials. Should a homeowner later decide to sell his property, the company would buy it back at the original purchase price, less rent for the time occupied. Always mindful of the importance of economic security, Nelson also established a provident fund to protect workers and their families from hardship in case of serious illness, injury, or death.

Most of the houses in Leclaire are modest, but attractive, frame structures. Elements of the then popular architectural styles may still be seen throughout the area – Queen Anne, Italianate, Gothic Revival, and Classical. It is likely that many of these features were mail-ordered from mill catalogs. None of the houses are truly grand or pretentious, however. Houses were generally one-story frame construction, averaging 900 square feet. More than half had hot air furnaces, running water, indoor plumbing, and electricity. They are more aptly described as comfortable and workmanlike, qualities which seem consistent with the values Nelson promoted.

When Leclaire was founded in 1890, architect R.E. Fallis was hired to design a portfolio of Gothic and Victorian house plans for the new cooperative village. Although home construction started immediately there were no homes sold in Leclaire until the following summer. For most Leclaire workers, home ownership was a new experience and it took some time for them to warm up to the idea. So the earliest houses were rented to workers as the community grew and eventually the concept of home ownership caught on.

Leclaire was open to any and all who wished to settle. Many had no connection with the company but lived there because they found the village agreeable. Employees were not required to live in the village. In fact, many were suspicious at first and chose to live elsewhere. But it was Nelson’s hope that his workers would be the principal inhabitants of the village.

The company operated a steam heated greenhouse and made plants and flowers available to the residents at no charge. Annual awards were presented for the best gardens. Anyone was allowed to keep a cow and poultry. The landscaping of the factory, the tree lined streets and the encouragement of flower gardening contributed to Nelson’s philosophy of beauty.

The School House

The second cornerstone of Leclaire was an educational system for the young and continuing education for adults. Nelson believed in combining manual training with academic education, calling it the development of the head and the hand. The educational opportunities were offered for free to residents and their neighbors in Edwardsville.

The schoolhouse was a spacious and attractive structure, in the style of a Chinese pagoda, and had four rooms. Partitions could be moved to expand it into a single hall for public meetings, dancing, and other social activities. The village’s library, containing over 1,400 volumes, was also housed there.

The school and the library were overseen by the Leclaire School and Library Association, whose members were resident homeowners in Leclaire. Both the school and the library were supported by company profits.

The formal educational system consisted of three steps. Kindergarten children were taught, among other things, the cultivation of flowers and vegetables. Between this age and twelve a regular school course was followed, supplemented by manual training.

At twelve, boys were given one hour of light work daily either in the factories or on the dairy farm and were paid a small stipend. The number of hours worked increased as the boys grew older. Girls were included but received domestic training in place of manual training. Education was designed so that a child, graduating at the age of eighteen, had received a sound classroom education while acquiring technical skills and work experience. If the graduate desired, employment was waiting for him with the company.

Recreation and Entertainment

Leclaire was not a place of all work and no play, and abundant recreational facilities were provided. An evening lecture series was presented at the school house during the winter.

Notable personalities such as Jane Addams of Hull House, Edward Everett Hale, and Sam Jones, were brought to Leclaire. There were regular concerts, debates, dramatizations, and lantern slide shows. Young people held dances on weekends. Men from the company organized a brass band which performed throughout the country.

For the more athletic, the village provided a billiard room and bowling alley, tennis courts, baseball and football. In the summer there was swimming and boating on Leclaire Lake; and in winter ice skating. On summer evenings, people gathered around the bandstand on the west shore to listen to concerts.

A Dream Ahead of Its Time

Nelson's interest in cooperation went beyond the founding of Leclaire. After 1911, when he was 66 years old, he launched a food cooperative in New Orleans after visiting the slums of that city and seeing the desperate need of the people living there. Soon he was spending most of his time in New Orleans developing the Nelson Cooperative Association and investing heavily in 63 retail grocery stores, a creamery, a bakery, a condiment factory, and a 1,580 acre plantation all of which provided a savings of 10 to 20% to 14,000 families.

Though initially successful, this enterprise experienced such great losses during World War I that, following its failure in 1918, Nelson filed for bankruptcy, pledging his stock in the company to pay for his debts. Nelson had financed the Cooperative Association by writing checks on the N.O. Nelson Company in St. Louis. These checks were charged against his stock in the company, but the leadership of the Company, notably Nelson's son-in-law, Louis D. Lawnin, did not support Nelson's efforts. Lawnin believed the company should stick to the plumbing supply business. Nelson was forced to resign from the company.

Leclaire thrived at first under the guiding hand of Nelson, though it never realized the full scope of his expectations. There were certainly families which found in Leclaire the better life of which they had dreamed. Others rejected Nelson's values and scorned the life of simple dignity and rationality he offered. It was these who were the source of Nelson’s ultimate disappointment and these, perhaps, who prompted the judgment of Nelson’s friend, Upton Sinclair.

“Leclaire was a dream ahead of its time.”

The ideas and ideals that Nelson put forth were progressive and perhaps revolutionary in the way that he attempted to address the social evils in the 19th century American capitalism and in the relationship between the worker and the employer. He proposed his system of cooperation not in a patronizing sense, but rather from the belief that given opportunity, proper living conditions, and education, the workingman could and would become the equal of the boss.

N.O. Nelson died in 1921, in Los Angeles, California at the age of 78.

Conclusion

Ironically, the same demand of modern cities to which Leclaire's founder owed his success, plumbing, forced the village to give up its independence. By 1933, Leclaire was nearly surrounded by a handful of new neighborhoods.

The added population and limited space made the disposal of sewage and other waste difficult. Edwardsville with a similar problem was developing a plan to improve its own waste disposal facilities. Late in the Summer of 1933, N.O. Nelson's grandson, Nelson Lawnin, suggested the annexation of Leclaire to Edwardsville as the best way to solve the village's sewer problems

On a January evening in 1934, with the adoption of ordinance No. 586 the City of Edwardsville annexed Leclaire, East Leclaire, Mahler Heights, Metcalf Addition and Guetlig Addition, in one day expanding Edwardsville's population by 2,000. The city assumed responsibility for Leclaire Lake and park. The Leclaire Kindergarten, campus, and the N.O. Nelson Memorial Fountain were to be transferred to the school district.

In 1979, the Historic Preservation Commission of the City of Edwardsville petitioned the U.S. Department of the Interior for recognition of Leclaire as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places. The nomination was approved thus establishing the Leclaire National Historic District.

Its import derives from the social and economic experiment that was undertaken by Nelson in the operation of the N.O. Nelson Manufacturing plant and the Village of Leclaire. What further distinguishes the Village, however, were the motivations for its development, and the commitment of the developer to higher principles.

Leclaire moves proudly into its second century with official acknowledgment of its unique contribution to American history.